Ci rivediamo! / We Will Meet Again! recognition | relation | action

Testo di Elena Bellantoni e Manuela Contino Progetto Grafico Elena Bellantoni e Fiamma Franchi

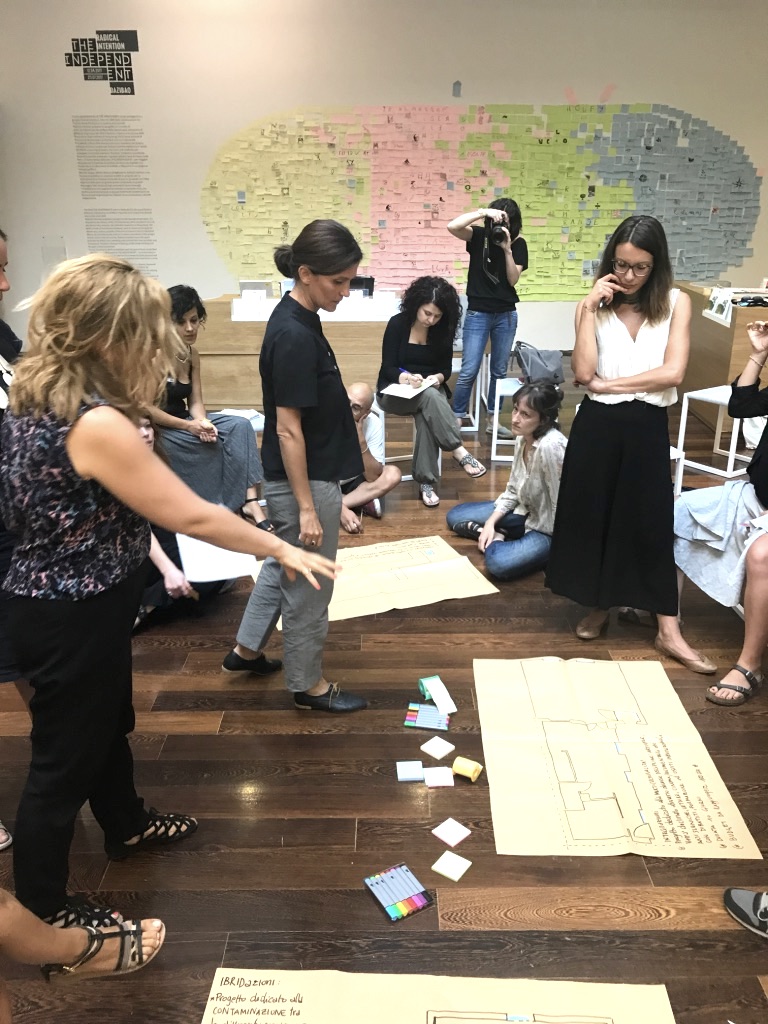

a workshop by Wunderbar Cultural Projects as part of The Independent program

Curated by Elena Bellantoni and Manuela Contino in collaboration with Radical Intention

Is the use of the term ‘non-for-profit space’ still viable for spaces in Rome today? Are questions around their whereabouts, their programming still important? Is it still possible to see them grow or are they being consumed? Do they still desire to engage with each other, or not?

And finally, is there a systematic reality, an organisational aptitude that is capable of triggering processes, which modify and create new practices? Can these new practices serve as forms of adaptation and model innovative and sustainable cultural productions?

Our task became that of being an aggregator of the so-called “off art spaces”, asking them to experiment group work methods and exercises of collective intelligence[1] with us for an afternoon. We finally asked them to position themselves on a map and create a new exchange platform.

We drew up an infinite list of names of potentially interested spaces, each withholding different aims and histories, some who are collectives of activists, others who compose a mosaic of strong experiences, others again who are sorts of meteorites, or rather spaces that are founded and closed within a season’s programming; a sort of fragmented reality, in which some don’t even know the existence of others, and which is made up of projects that, despite all difficulties, continue to write their own history and that of the territories they belong to.

We questioned how this situation could be outlined, given in Rome plans are not programmatic, perspectives are not systematic, and therefore do not unify, and people rarely play by well-defined rules.

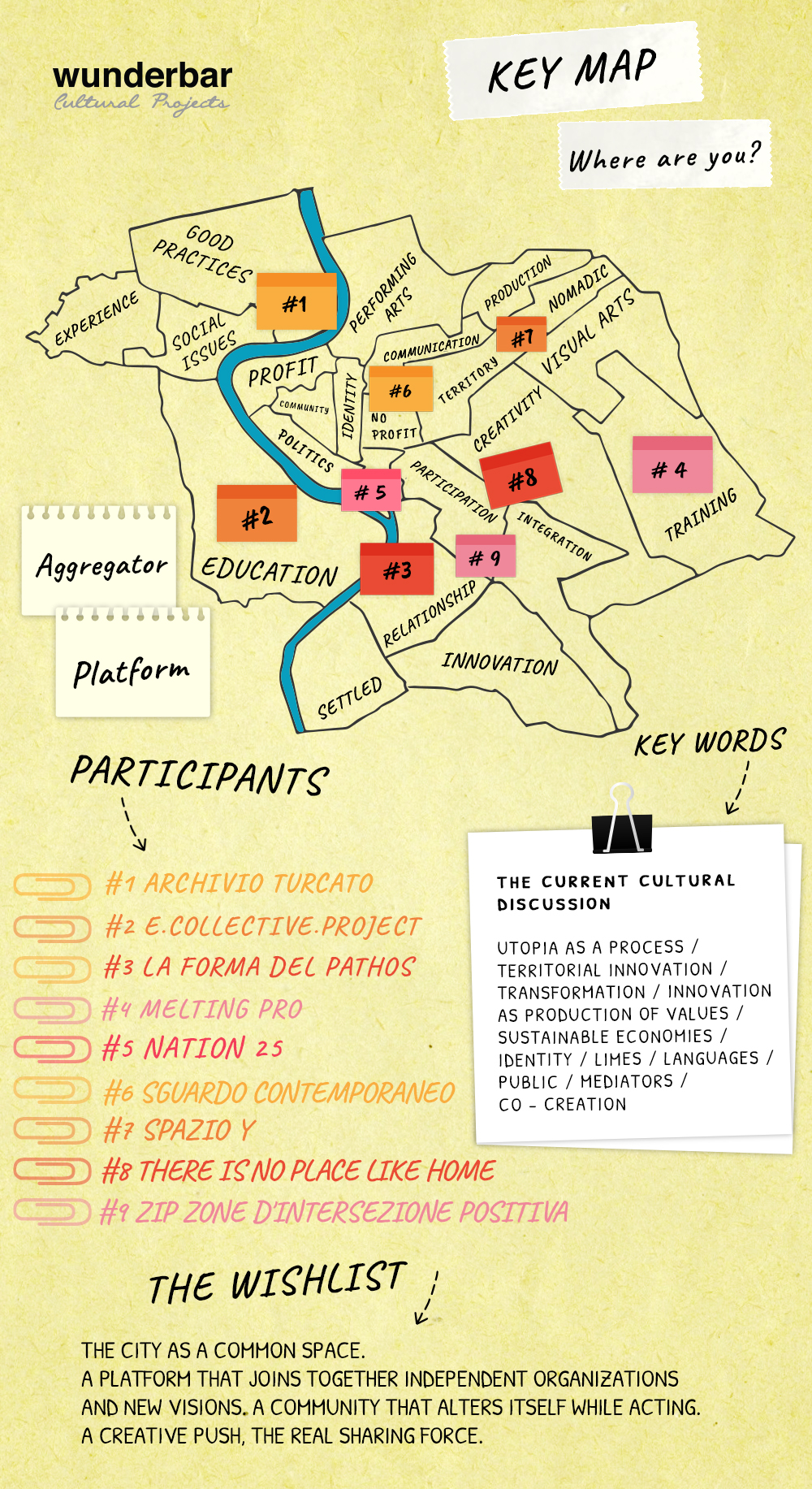

We told ourselves that if physically mapping key figures of this fragmented system it is too complicated, because it is made up of too many square kilometres, where north, south and east and west neighbourhoods are divided by clearly marked cultural and social boundaries, then our map will be conceptual, rather made up of words and self-defining paths than geographies.

We therefore see the city as an enormous body in motion, able to hybridise itself, which, through projects, gives back to its own territory the value of withholding all needs and desires of the community[2] of interest.

These ideas constructed the Ci Rivediamo! / We Will Meet Again! workshop and defined our aim of trying to understand the reasons and urgencies that weave into the fabric of Rome, sparking our interest in collaborative process and shared workspaces situated in the cultural system of the city[3].

Each organisation positioned itself on our map, and used a few key words – taken from terminology of the spheres of cultural programming and processes of artistic creation – to define their identity. Each organisation presented itself to others through their choices, but also, through their perspectives as contemporary artists, revealed a city that is fragmented.

Although contemporary participatory tools (such as the technological ones, such as online platforms and collaborative networks) should theoretically contribute to a weakening of the various forms of individualism, many of the so-called participatory cultural projects merely tackle the issue formally, therefore struggle with the development of a feeling of community or promote innovation.

The organisations involved in the workshop, followed a tailor made display after pragmatically responding to a series of questionnaires and finally interacted with each other by hypothetically developing projects for different spaces across the city and simultaneously thinking of a new model of community.

In the late eighties in Italy and France, a debate around the category of community challenged a paradigm of contemporary philosophy, for which ‘community’ was the substance connecting certain subjects to one another, in virtue of sharing a common identity. he notion of community conceptually resembled that of “property”: either taking possession of that, which is in common, or turning something one owns into a shared resource, , the community remained defined by a reciprocal appurtenance. Its members possessions where shared, and they owned what they had in common[4]. A series of texts[5], including The Inoperative Community by Jean-Luc Nancy, The Unavowable Community by Maurice Blanchot, The Coming Community by Giorgio Agamben and Communitas: the Origin and Destiny of Community by Roberto Esposito argued against this conceptual short-circuit, forwarding notions of community as a sort of constitutive alterity, avoiding o any connotations of identity.

The notion of community is very ambiguous and complex, and should be included in critical discourses on globalisation, which, as Bauman[6] argues, has produced a flattened society, creating ‘loneliness and discomfort’. The individual’s desire to belong within a group and be reciprocally part of it, is thus understandable. There are communities that last for a lifetime and those that last for a single day; the later’s formation is due to a an urgency of disorientation between the desire for an individual space and the desire to be part of a group. In Community. Seeking Safety in an Insecure World (2001), Bauman analyses the relationship between individual and society, between single and collective.

The community outlives the place, it defines where we were born, the environment we feel comfortable in, the community binds us, protects us, it is solid and present, it can be hard to please. Society is the whole world, the disorientation and loneliness.

The we can question ourselves on how community can set us free. Communities generates solidarity, but only amongst individuals of the same “class”; it creates uniformity, as in solidarity we share the same problems. Those living in the community assume put the same uniform on. The relationship between the inclusivity of the community and the exclusivity of identity is ambiguous. Therefore communities can become cages, or an obligations.

Community is the word of the century! One of the etymologies of the word is cum-munus, or with-duty’, suggesting that ‘community’ is as relation rather than substance; as expropriation and not appropriation. What is communal is that which is not our own. By thinking of a definition in these terms, we come up with words and phrases like “common good”, “belonging”, which are characterised by a feeling of having in common.

We are interested in turning this perspective upside down – acknowledging the theory of Roberto Esposito[7] – and characterising a community as a series of members, whom are not united by a common property but, on the contrary, by all having a “debt”, a lack of something that consists in giving something of oneself to the others. The community that we envisage stems from an emptying out of properties, it forces the subject to alter himself to come out of himself. This is why, according to us, we must alter ourselves!

How? Through regular meetings with different city stakeholders, at which the proposed actions are co-created, co-decided and planned, where invitees work on open source platforms and innovation labs, and aim at starting to re-know and lay the groundwork for a new model of cultural and social innovation. The community‘s subject, thus, becomes a “non subject”, given the risk of losing its individuality and slipping into nothingness. This nothingness becomes the constitutive element of the community, or rather a moment in which it stops being a collective subject, and instead it becomes relationship and encounter[8]:

“So… When will we meet again?”.

WUNDERBAR Cultural Projects is a cultural association born from the shared intentions of five professionals from the worlds of creativity, art and culture: two visual artists, two cultural project managers and a graphic designer. We design and realise sustainable activities that may have a social innovation impact in the areas in which they take place, through the supply and use of methodologies based on cultural knowledge, creativity and participation. Wunderbar believes in a precise way of thinking that sees Art, Culture and Education as important tools of knowledge and recognition of the present in which we live.

Workshop participants:

MELTING PRO

An organisation that supports companies in putting together strategies, projects and models that aim to develop territories, communities and people. It facilitates alliances, network building and collaboration between companies on a nation and international level. It carries out research and activities in the following fields: urban regeneration; audience development; empowerment and training for the cultural sector. www.meltingpro.org

SGUARDO CONTEMPORANEO

An association formed by art historians and curators, whose research and activities are directed towards the broadening and differentiation of the contexts dedicated to art, to its production and its enjoyment, to the reflection on the relationship between art and the social and urban fabric of the city, to its neighbourhoods and its cultural heritage, to the promotion and realisation of projects with site specific and socially engaged approaches. www.sguardocontemporaneo.it

FONDAZIONE TURCATO

Born with the mission to foster greater public interest in the role of the artist as an agent of social transformation. Amongst its objectives is the creation of a network of connections that will elicit an inclusive cultural dialogue through educational programmes. Taking inspiration from the legacy of the artist, the Foundation sees itself as a place in which projects with the following subjects can converge: the creative process, science, politics, ecology, psychological distress and diversity.

http://turcato.org/

SPAZIO Y

An independent space dedicated to research and experimentation in contemporary art and a meeting point for artists and those working in the cultural sector, invited from time to time to interact with the context in which the space is located and active in. Created in 2014 by a collective of artists, it has organised more than thirty events, produced site specific works, relational art projects, actions and performances.

www.spazioy.com

THERE IS NO PLACE LIKE HOME

An itinerant project that started in Rome in 2014. The name metaphorically includes the nomadic character of the initiative and, at the same time, the desire to construct exhibitions that are in close dialogue with their chosen space, to transform it – over the selected period of time – into a lively cultural destination, activating and enhancing the place itself and making it a frame-container of the vision of the artists sometimes invited to it. https://www.facebook.com/thereisnoplacelikehomeproject/

Zip_Zone d’intersezione positiva

Born from a meeting of professionals from different fields, all with a common conviction that Culture, Art and their various modes of expression can be shown to be tools of action and creation in all parts of society. It plans and realises courses, activities, moments for debate and growth, as well as recreational and social events intended for all citizens.

ECOLLECTIVE

The “e” of ecollective refers to education, experience, energy, elaboration, e-generation. It promotes knowledge of contemporary artistic languages to a diverse audience: art becomes a tool for analysis, reflection and expression. Surveying the world of contemporary art generates new listening skills and stimulates creativity that, in a collaborative learning context, enriches our everyday lives.

www.ecollectiveassociazione.com

NATION 25

Nation25 is an artistic-curatorial platform founded in 2015 by Elena Abbiatici, Sara Alberani and Caterina Pecchioli, and it aims to shine a light on experiences of migration and invisibility and what they can lead to. The name refers to the 25th nation on earth, a nation both imaginary and real, made up of the 60 million individuals that have been forced to leave their countries because of war and racial and gender violence. Instead of the principle of citizenship based on geography, Nation25 proposes one based on common rights and needs.

LA FORMA DEL PATHOS

La Forma del Pathos is set up as a platform for debate and reflection on performance in the visual arts in the city of Rome. It started with a core group of artists and a curator – Gianluca Brogna – but has gradually expanded to include other artists, from the visual arts and other fields (theatre and dance). The group is characterised by the location they have chosen for their performative actions: they have abandoned museum exhibition space for the theatre.

[1] Pierre Levy (2004) stated that collective intelligence is an intelligence that is constantly enhanced, coordinated in real time and that results in the effective mobilisation of skills. It is shared and therefore appreciated.

[2] Understanding the city as a place that values inhabitants’ collective intelligence calls for a paradigm shift that is capable of producing a set of procedural and operational tools meant for those who accept the challenge and overthrow a sterile and not very innovative vision e. Defining a new agency and alternative and more profitable vision, one that is capable of renewing and enhancing idea of the city as a platform for enabling human capabilities, as an accelerator of empowerment and as a multiplier of human capital (Maurizio Carta, The Augmented City. A paradigm shift, 2017).

[3] The individualist approach to creativity overestimates the role of the individual and of his/her abilities (the myth of the genius). On the contrary, the socio-cultural approach emphasizes the role of contexts in the creation process: societies, cultures and historical periods. Accordingly, the individual is seen as a member of many overlapping social groups, each of them with with its own specifically structured and organized network, which influences the creation of oher networks of—potentially creative ideas. Each individual is also a part of a certain a culture, which offers specific categories he/she uses to understand the world. Finally, each individual is representative of a specific historical period. Creativity is therefore ‘‘situated’’ in specific contexts (Managing Situated Creativity in Cultural Industries Fiorenza Belussi & Silvia Rita Sedita, 2008).

[4] Cf. R. Esposito, Communitas: the Origin and Destiny of Community, Stanford University Press, 2004.

[5] On the sociological side of the discussion, A. Bonomi, Sotto la pelle dello Stato. Rancore, cura, operosità (Under the skin of the State. Rancour, care, industry), Milan, Feltrinelli, 2010 utilises the category of community to describe the current phase of Italian politics.

[6] Zygmunt Bauman, one of the sharpest thinkers of our times, recently deceased. Best known for his striking definitions of a modernity in which everything is “liquid” (life, love, fear itself), ambiguous and fleeting; to say it with a misused word of today, “precarious”. In his book Community: Seeking Safety in an Insecure World (Wiley & Sons Ltd, london 2001) he highlights a nearly instinctual and forever present desire for community that compensates the underlying insecurity, which is a paradigm of a globalised world in name of f liberalisation, flexibility, competitiveness and individualism. However, in this search for community, or rather an unavoidable and ancestral human need, we always find ourselves trying to cling to something that is fleeting. slips just out of reach. “Like this we continue to dream, to try and to fail”, writes Bauman. And, unfortunately, we are less and less aware that this destiny is everyone’s, not just each of us in our own personal sphere. “Each of us consumes our anxiety alone, living it as an individual problem, the result of personal failures and a challenge to our individual skills and abilities”, writes Bauman.

In recent years, Zygmunt Bauman’s participation and theoretical contributions of to the debate on globalisation has been fundamental. . After carefully analysing the post-modern era and the consequences of globalisation on individuals (see the book Globalization: The Human Consequences, Polity Press, Cambridge, 1998), Bauman particularly focusedon the collective dimension of this process: on its current limits and the difficulties of it’s implementation, resulting from requesting in a claim for a livable community amongst men; a request that nevertheless must be considered a fundamental demand and need. Bauman wants to show us the future dissolution of “real” community (peasants, artisans, traders, etc.) and the torment and agony of having to live in the grip of insecurity, while always yearning, as the descendants of Adam and Eve, for the ideal community, the one we dream of.

In this brief and theoretically dense essay, he explains how we seek personal solutions to systemic contradictions, salvation in the singular forms problems that can only be solved collectively, falling back on our own resources and further fuelling the world’s insecurity about those that are “other than us”, the strangers. The dream of community seems to simplify life because it makes sure that each of us forges relationships only with those that are “similar”, in settings, where common identity means we can feel less alone and be surrounded by the “protection” and recognition that only a homogeneous group can offer. Even if this means excluding from our sphere of interest not only that which does not concern us, but also the broad margins of our own freedom to be “other” than the image of ourselves that we have built to relate to others.

On the other hand, what would really help us create the foundations on which we can build a true feeling of community is, according to Bauman, first and foremost a real equality of resources – without this, we are de facto citizens, but not citizens by rights. Secondly, we need collective insurance against individual misfortunes and adversity. Unfortunately, the unique thought of our society does not care about these proposals and openly proclaims them to be counterproductive, which ends up making the individual feel the weight of his failures as well as that of the “creation” of a destiny based on a fragile and necessarily insufficient voluntarism. However, as Bauman reminds us in his short and intense book, which tackles the today’s’ challenges, that of first and foremost moving from equality to multiculturalism, if there is ever to be a community in the world of individuals, it can only be one that it is “responsible, aiming at guaranteeing equal rights to every human being and equal capacities to act upon the basis of that right”.

[7] Esposito’s analysis focuses on the etymology of the Latin term communitas:that which the unthinkable of the concept community lurks in this term, or rather its paradoxical truth. Here, in a very brief summary of Esposito’s research (to explore this further, see Communitas: the Origin and Destiny of Community, Stanford University Press, 2004), it can be said that the term munus (from communitas: cum – munus), which originally signified duty or obligation and which, in the last analysis, denotes that which is not property, the opposite of property, that which starts where property ends.

“… the munus that the communitas shares isn’t a property or a possession [appartenenza].11 It isn’t having, but on the contrary, is a debt, a pledge, a gift that is to be given, and that therefore will establish a lack.” (Ibidem).

[8] According to Esposito (cf. Communitas: the Origin and Destiny of Community, Stanford University Press, 2004) what binds the subjects in the community, therefore, has nothing reassuring about it, it is not perceived by them as painless, since it seems to be characterised as their end, their death. From this comes the temptation, translated into reality in modern philosophy, to confront the danger of the munus and to proceed to its immunisation. In the new philosophical vocabulary proposed by Esposito, immunitas is the opposite of communitas. It is precisely the opposition between these two terms that allows him to attempt a new reading of existing philosophical thought on community and, in this way, to rewrite a part of the history of philosophy.