A conversation between Elena Motisi and Fabio Alfano

Elena Motisi, Fabio Alfano

Elena Motisi: What does the label of “independent” mean for you? Why do you define yourselves in such a way?

Fabio Alfano: I’d like to start by saying that Centro Studi Anghelos has various components: the ones that fall within this area of research are ‘anghelos a.a.a. living art architecture’ (anghelos a.a.a. abitare arte architettura) and the ‘citizens’ committee for the collective good’, although the same general principles apply across all the components.

‘Independent’ means not belonging to or depending on any institution – be it public, private, educational, political, etc. – in any field, being able to bring forward ideas and projects that are free from any kind of conditions.

Regarding our work group, the core of the Study Centre is made up of my brother Marco and myself; from time to time, dependent on projects, we involve other parties. As an architect, I mainly work on urban issues.

How does the concept of independence intersect with the fields of architecture and urbanism? How does this affect the profession and its projects?

I believe that, at the moment, architecture and urbanism, understood as professional disciplines, are not very independent (especially in Italy, and particularly in the South), in as much as they are subservient to the interests of administrations and governments, but also to the private sector, and this degrades their architectural and urbanist quality. That which does remain independent is beauty – architectural, urbanist – which, despite everything, survives as an innate need within people.

The tools of ‘independent’ architects are definitely different, as they have to make up for an absolute absence of economic resources with creativity, invention, ‘do it yourself’ attitudes, etc…

Is it possible to talk about non-profit work in your fields of activity?

Absolutely. And that’s a fact. This shows that it is possible to work without profit, to follow an ideal, out of a strong need for change, because you consider it necessary to fulfil a role that no one else is. If we all learnt to make our expertise, skills, resources available to serve a ‘collective good’ from which everyone – including ourselves – would benefit, things would change much more quickly.

In my opinion, emergencies can be a source of inspiration for new architectural projects. Do today’s independents have to come up with new topics for projects of their own accord, relative to the needs arising from the context in which they live? In this respect, identifying one criticism and one opportunity, is it possible to respond with the processes on which self-initiated projects are based? Under what conditions, then, can a “self-commissioned” project exist?

In Italy, and in particular in Sicily, there are endless swathes of land – urban and suburban – to rehabilitate, redevelop, reinvent, and there is an absolute lack of administration and governance with which to do so. And thus, right now, it is absolutely necessary to use ideas and projects originating from the bottom up to overcome this deficiency; projects and ideas that can identify “key locations”, recognising their basic needs and knowing how to transform them into programmes of work that will initiate processes of change, as well as a search for resources.

With regards to ways of working: what does working with citizens mean to you? What strategies are available for shared work?

Our cities are made up of large houses, broken but lived in, and those who live in them no longer tolerate orders from above, in which they no longer have any faith. Already so far over the limits of their endurance, citizens want to be actively involved in the processes that are transforming the spaces that they are a part of.

It is necessary to give them a role. What is this role? Certainly it’s not realising projects, which is the job of architects. Instead, it is to express their housing needs and, in the final phase, to take part in choosing between the best projects devised by the architects, in order to turn their ‘needs’ into ‘spaces’.

Therefore, cities have to transform themselves through a collaborative and synergistic interaction between citizenship, professionalism and administration; the latter has the role of coordinating and bringing forward these integrated processes.

In my opinion, there are some subjects, such as the emergencies related to migrants (possible solutions for receiving them,…), construction waste and its disposal (alternative uses of the unfinished,…), the critical relationship with territory (urban gardens,…) and the generalised political crisis, which may be considered as the starting point for independent collectives’ planning of activities. What is your opinion? Do you think that the solution to these issues can be found in an institutional context or, rather, outside of it?

The issues that you mention are certainly ones of great relevance and urgency, and are at the heart of the initiatives of many individuals active in the field, including us. The solution to these problems must absolutely come from institutions, but certainly not from those we have at the moment, which are not able – and moreover are not interested – in resolving them.

The work that is taking place from the bottom up, from the personal initiatives of small and large groups, from the architects that you call ‘independent’, really serves as a testament to this criticality. It underlines the inability of the current ruling class to resolve the issues, their inability to show solutions and possible methods, and it affirms the need for a radical overhaul of those occupying positions of institutional power.

How much does politics affect your job? Does political pressure represent an incentive or a barrier for independent architects?

Currently, the position of politics is paradoxical: it is a limit, in the sense that it doesn’t act or make others act, but it is also a strong stimulus, as it is potentially the principal motivation for our work. This is because it is so far removed and such an obstacle to attaining objectives such as quality, beauty, architecture or the common good, that it compels us to take the field, even taking on roles we wouldn’t normally assume. That’s how we came to do the work that we are currently bringing forward.

Do you think there is a connection between those territories characterised by conflict and the presence of independent groups? Can we say that the intensity of the presence of these collectives and of their actions tends to superimpose itself on maps of emergencies and geopolitical imbalances? Is there a relationship between the conditions of conflict in which they work and the way in which architectural planning paradigms change?

Definitely, there’s a strong correspondence: the greater the emergencies and the conflicts, the greater the need to intervene and the more groups that are formed. Here in Palermo, for example, many new committees, collectives and associations have been born; many of these, however, have had a short life.

Of course, the paradigm of architectural design changes, not with respect to universal instances of architecture, but with respect to the way in which it is implemented, the processes, the parties involved and its purpose.

Talking about strategies, do an unambiguous and independent way of planning, or some guidelines that can act as a tool for a new kind of intervention in line with the needs of the contemporary, exist?

A single, unambiguous process for independent design cannot exist; recurring themes, common principles, fixed methods of intervention can. These are the ‘participation’ and the ‘collaboration’ that we have already indicated are our preferred methods. There are also urban interventions on a micro scale – easier to handle – or reuse, recycling, eco-friendly behaviours, sustainability, returning to nature, principles that are always increasingly felt.

Which of your projects has represented an effective action within the field of the topics you investigate? Could you briefly describe it?

In the field of projects directly related to architecture, I would say the ‘urban micro redevelopment competitions’ organised in recent years. These were tasked with displaying virtuous processes applied within tiny urban fragments, but which had the potential to be extended to the various ‘scales’ of the city. These competitions produced solutions founded on ‘participation’, they identified the necessary professional disciplines (for example, the architects involved through the Order) and put them in touch with the relevant municipal administration. The competitions were carried out in the best possible way: they involved citizens, who enthusiastically expressed their needs and participated (online) in the final phase, the selection of the winning projects. The only part that didn’t work was that relating to the Municipality. Notwithstanding the agreements that had been made (for realisation through public works) and the fact that the Municipality was under no obligation to finance such projects, they didn’t realise them, totally wasting all the work that had been done.

I would also like to mention two important and innovative projects of a more general character. One is the drafting of a new municipal Statute for the city of Palermo: ‘Governing with citizens’ – by ourselves and many other civic organisations. Its objective is to define a new administrative model that has obligations for shared planning, the effective participation of citizens, transparent actions and quality choices. This new Statute[1], which would also revolutionise the way in which the physical transformation of the city is realised, is finding – as expected – a series of obstacles to its approval. Nonetheless, it has definitely kicked off a great process of cultural change in the city and, above all, has raised citizens’ awareness of their rights and their power.

Another ongoing project is the ‘SOS Palermo Beauty necessary’ appeal’[2], signed by hundreds of architects, amongst others. It denounces the disaster in architecture, urban planning and environmental protection that the city has seen in recent years. It affirms the right of Palermo’s citizens to re-appropriate the city’s lost beauty, creates a ‘Palermo question’ that is visible on a national and an international scale, and defines and proposes new solutions for the city, from a range of perspectives: administrative (related to the new statute I mentioned), architectural and urbanist.

Working in “crisis” areas results in changes to the timescales for design projects: have you found that there is any relationship between the acceleration of such timescales and the innovativeness of the results?

It can take a very long time because some steps in the process cannot be controlled since they depend on others, administrations for example. Sometimes the process cannot be completed, like in the case of the micro-redevelopments I mentioned. However, this doesn’t matter too much as, at this point in time, showing ‘processes’ is just as important as exhibiting ‘results’.

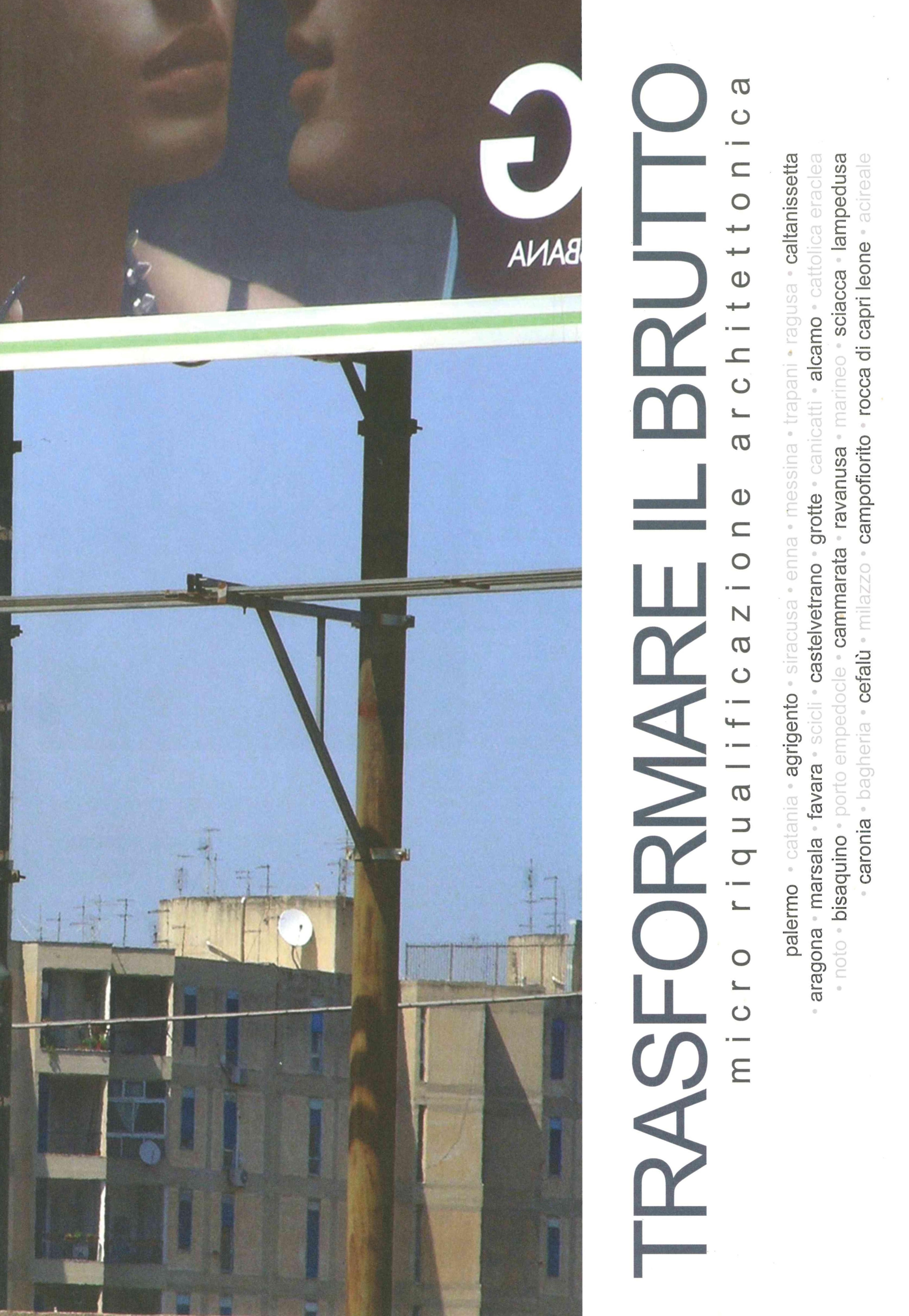

Can you tell us a little bit about your project of micro architectural requalification TRASFORMARE IL BRUTTO?

‘Transforming the ugly’ (Trasformare il brutto)[3] is a publication/manifesto about a possibility and necessity, but also about something currently underway in Palermo and Sicily more generally: the ‘transformation’ of the ugliness realised from the post-war period up until the present day. It is a collection of articles, university projects as well as some by professionals and citizens, that describe how it is possible to give architectural quality to the banal and vulgar buildings currently in existence (residential buildings, the so-called ‘condominio’) and to a series of urban micro-areas that have never had any distinct identity. We give this publication to citizens for free and, through it, they can understand that transformation is possible.

Are the themes you deal with in your work related to those urgent issues which are inherent in your country and in the territories in which you operate. In this sense, does the fact that you are islanders represent a limit or an opportunity?

Yes, as I said before, the themes that we deal with are tightly related to where we’re from, our territory. If there wasn’t this devastation, this immense deterioration, this unbearable amount of ugliness and total absence of architectural culture and quality, our activity wouldn’t make any sense.

Being islanders is definitely a limit, in as much as in being ‘isolated’ we can’t enjoy the many opportunities that better connected territories have, on a cognitive level, for experiences and exchanges, etc.. At the same time, however, it holds great potential: being part of a time, a society, a reality, but at the same time being slightly detached, allows for a privileged point of view that generates – where there is a need – processes of change that would be unthinkable elsewhere. On an island you are part of the ‘world’ but, thanks to a physical detachment, you are also an ‘observer’ of this world and its processes.

And then in Sicily, for historical reasons, there is also an exaggeration of processes that appear completely obvious and, for the most part, analysable. On this island, everything is over the top: very good times and conditions (for example, the Norman or Florio periods) have alternated with totally negative times and phenomena (oppressive rulers, the mafia, etc.). There is no middle ground. When change becomes necessary, its possibility of being realised is maximised by a detached gaze and a patency that allows for an easier identification of the elements on which to base the transformation.

It would be very difficult for what has happened in Sicily in the past, and what will most likely happen there in the future, to happen in other territories with different characteristics.

Your group works primarily in Palermo. Was this a choice? What are the reasons behind this?

We work in Palermo first and foremost because it is where we were born, because, as we said, a large part of what we do is strictly related to the specific issues of this area, because here you must and can do things that are not necessary elsewhere and which, in any case, could not be implemented elsewhere.

An extreme disharmony reigns supreme in Sicily, on both an ‘aesthetic’ and, obviously, an ‘ethical’ level (one being a consequence of the other). Our work strives for a reawakening of people’s awareness of the need for an ethical and aesthetic harmony that brings us to the view of beauty as a necessary prerequisite. Until now, we have been deceived by the illusion that we are separate from our surroundings, and this assumption has legitimised ugliness.

What we are doing here, this ‘Palermo laboratory’, could certainly constitute an example, available to all who want to observe and imitate it. Through this, perhaps, Palermo will reacquire the national and international position it once had.