Civility?

Huang Jingyuan

After co-founding an artist-run center in Beijing’s Caochangdi art district in 2010, I continued to run it briefly until 2012, and then afterwards returned full-time to my activities as an artist. Since then I have collaborated on projects with independent art spaces in Beijing and elsewhere. The evolution (and struggles) of independent art spaces and the role of art in community building have been crucial to my understanding of art and my practice as an artist. My experience tells me that, in the most rewarding cases, the nature of the chosen project personalizes, interrogates, and challenges the hosting art space, and in return, the art space provides facilitation, mediation, and a critical framework, forming its own identity based on the collection of projects it supports. But this is based on the assumption that these spaces are somehow stable: that at least they can operate at a designated physical location that allows them to manage the flow of projects that come and go. Around 2016, this necessary stability had become even more precarious after a new Beijing city management policy insensitively disrupted many citizens’ lives and businesses in both the Hutongs (old downtown residential areas) and Five-ring road areas at the outer edge of the city where artists have congregated.

It is within this context that my project Civility Trilogy emerged. It was initiated by invitations that were received over a short period of time from three different types of independent art spaces, and was followed by a quick decision: I want to not only make a project that happens in independent art spaces in Beijing, but also a project about independent art spaces in Beijing. I wanted to use the artist’s gesture to link these three locations in order to address their potentials in creating publics, and underscore the fragility of each location. For me, the idea of forming a “trilogy” is a type of “infrastructure,” one that seeks to compensate for the lack of an infrastructure for addressing the public at various art spaces.

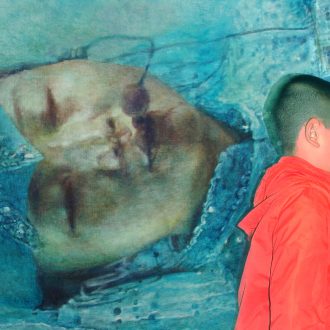

Formally, the Civility trilogy is three successive displays of large-scale portraits in centers that because of their size are neither ideal nor expected to present large canvas works. It was my attempt to highlight and activate each of their awkward spaces and realize hidden potentials in forming a “public” place. I regard creating the proper “viewing distance” of a painting, in both the literal and abstract sense, as having the potential of creating the experience of civil life. Civil life is something that relies on and yet creates a “public” place; it is what is terribly missing in government’s current directing of citizens’ live.

The first installment of the Civility project started in November 2015 at the Aotu Space (a high-end hair salon in a downtown hutong neighborhood), with the last installment occurring in early July 2016 at Lab 47. The second installment took place in an art space called The Office. It is located in a claustrophobic commercial booth in a Wangjing commercial building in Beijing. My process began by examining the preexisting features of the location; I then selected particular images, tailored their scale so they would engage with the space in an unusual way, and then painted and presented them in situ.

From the experience of creating the Civility trilogy, I came to understand that the context for the presentation of large portrait paintings (in public) can have a significant impact on the impression it creates for the viewer. It can be a dominating experience, or in other situations a source of strength, maybe even an exposure to possibilities that people have, but are not aware of. For me to tap into this experience is so vital, especially in a country with a shrinking civil society, and shrinking public spaces, and I cannot do that without the help of art spaces that merge with the social fabric of the local community. At the moment that I am drafting this essay, two spaces that I had worked with on this trilogy have closed, and the only one left has had its second floor demolished. This is only a small reflection of the much larger and fierce process of elimination, ranging from the possibilities for daily existence to the possibilities for art.