Dazibao

Radical Intention

In Radical Intention’s discussion of December 2016 with Giulia Ferracci, curator of THE INDEPENDENT program, the group analysed a new shared meaning of the word independent. The dialogue with an art institution, such as the MAXXI Museum of Rome, naturally led our independent group to question the meaning of this term. The final result of this discussion is the DAZIBAO project, a platform including a homonymous participatory installation, a temporary office and studio, and a public program inviting experts to discuss independence and self-organisation in contemporary socially-engaged art. DAZIBAO studies the limits of participatory processes through practice, and this issue of online magazine Garibaldi complements this study and provides the group with an opportunity to deepen their research on the relations between notions of discursive platforms and democratic participation processes.

On the occasion of DAZIBAO, our artistic/curatorial group measured itself with its own history – by archiving and editing materials for its new website radicalintention.org – and with its methodology, by further experimenting with its own performative actions and group work exercises, which have accompanied its practice since its foundation in Milan in 2009 to the organisation of Decompression Gathering Summer Camp, a biennial workshop at Corniolo Art Platform launched in 2012. The desires and interests underlying our practice, emerged more clearly during the realisation of DAZIBAO. We enhanced our approach to the creation of functional platforms, which can host the search of common feelings, the creation of research groups, the analysis of commoning processes amongst groups, the relations between individuals and society, and society’s relationship with time. These are some of the themes that further defined DAZIBAO, developed our practice, conveyed our feelings and thoughts.

The source of inspiration for this research is embodied by the DAZIBAO. In China, the Dazibao was a public means of communication, a sort of bulletin board containing posters and handwritten messages. By the use of hand-painted posters and slogans, pedestrians were informed about the essence of the political theory. The Dazibao was a primary means for communicating intellectual dissent up until the 1979 cultural revolution, after which it was forbid. A group of students protesting against the Chinese domination in Hong Kong, promoted a new take on the Dazibao in 2014; this student movement, called the Umbrella Movement (owing to its using an umbrella as a symbol of struggle) proposed its own version of the Dazibao and called it the Democracy Wall, a 1-km-long wall made of written post-its containing messages of solidarity and freedom of expression. We hypothesized that replacing an artefact, which required a long and pondered production process, with post-its, which are much quicker to create, use and read, is not only the result of a profound shift in communication and language structures but also underlines the ephemeral nature of today’s communication.

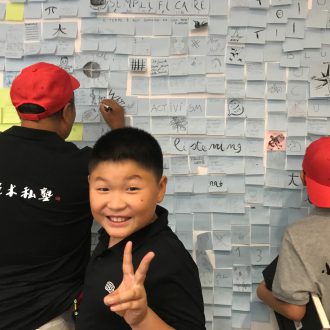

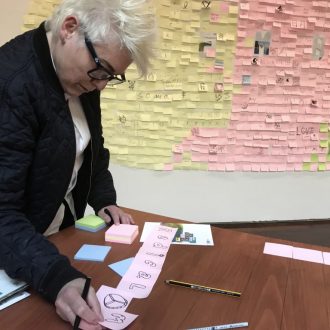

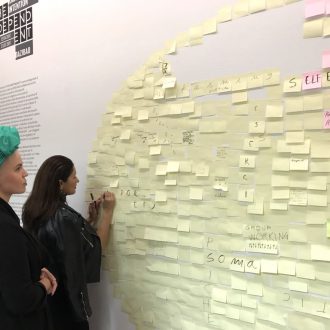

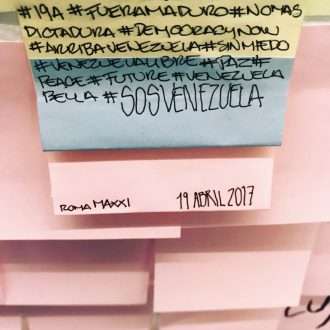

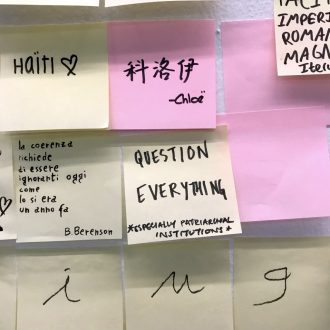

Building upon these reflections, Radical Intention proposes its own version of the Democracy Wall. The DAZIBAO installation presented for THE INDEPENDENT makes use of post-its as a medium to transmit written or drawn messages or thoughts. This form of the Democracy Wall is a work-in-progress and artistic project. At MAXXI it served as a background to Radical Intention’s public program, and the Museum’s exhibitions. We invited our audience to participate by contributing with post-its to our installation, and hanging them on the wall so as to create a complex collection of statements and messages communicating different emotions, and finally, turning the wall into sort of a collective organism made of individual interventions. A little by chance, a little by choice, the DAZIBAO took on the shape of a planisphere, as though it were a sort of collective map, embodying the complexity and diversity of the visitors to the Museum.

In time, the progress of our Democracy Wall became a source of inspiration to understand ways whereby the public interacted with our proposal. We wondered what sort of enthusiasm, affectivity or interest people had when participating in a collective project, its chameleonic and ever-changing meaning prevented its complete understanding. What would they like to say, and who are they speaking to? Is it to other visitors at the Museum, or to their own social networks and followers, whom they inform in real time about the wall’s transformations? What is the nature of these written messages? Are they political messages? Do they express dissent? Do they express social urgency? This series of reflections led us to understanding this platform as an open, flowing source of contradictory content, a sort of “communicative chaos” that spread across the Museum, and across the web.

Nevertheless, the Dazibao is still a wall, namely a means to delimit and separate space. The planisphere-like shape of our wall contained the visitors’ words and images, while they partook in the Museum’s life. A wall acquires important meanings: it is a symbol of separation and alienation, as in the case of the wall between Palestine and Israel, the one between the United States and Mexico, or the sea, which is perceived as a barrier hindering migration towards Europe. Thinking of the wall as a border prompted some visitors to leave a clear, simple political message aimed at tearing down barriers. A post-it reading ‘no borders, refugees welcome’, written by an English teacher, was placed outside the perimeter of our planisphere, as though it represented what lies beyond the installation, the wall, and even beyond the group’s creative impositions. This sort of “political relevance” could also be inferred from a message of solidarity towards the struggles of Venezuela, which, at the time of our collaboration with MAXXI, was experiencing violent street clashes due to the popular opposition to president Maduro’s policies. Therefore, by encompassing both local and international situations, our planisphere of post-its embraced the world in its entirety. While the Democracy Wall contains political messages, the planisphere expands conceptually by adding messages of and quotes by famous authors about travelling, fantastic drawings and symbols, such as the Tao or unicorns, but also messages of protest against the Italian capital’s government.

When taking part in the installation of this wall, individuals contributed to a collective effort, whereby messages were lost in this communicative chaos of colourful post-its. During the participatory process, we were able to notice a certain possessive relationship some participants had with their own messages, which caused a misunderstanding of the collective and overall value of the installation. Given today’s social structuring, social-media’s modification of communication, and the current culture of individualism, the attention some individuals leaned rather towards virtual worlds than the ‘here and now’; all their effort to speak to their social networks therefore was put into taking a unique photo, of their unique post-it.

We argue, this kind of protagonism symbolises society, wherein the web filters democratic processes, and people belong to groups thanks to others and their approval. By offering visitors freedom and autonomy with DAZIBAO, we expressed our take on democratic processes enabling every piece (post-it) to establish a connection with the others, regardless of approval.

Therefore, Radical Intention’s DAZIBAO contributes to discourses on participatory processes, by enacting their limits, challenges and future opportunities. The delicate, ever-changing relationship between individuals and society is represented, shared and analysed thanks to this version of the Democracy Wall. The goal of the project remains carrying out research, both collective and participatory, aimed not so much at providing answers, but rather at bringing about new nuances, concepts, ideas and methodologies thanks to the cooperation of participants. This platform is made up of democratic processes where the very concept of democracy is questioned, acceptance is not the goal, and immediacy does not necessarily go against the possibility of building communities.

We invited to contribute to this issue Simone Ciglia, Emanuele De Donno, Sarrita Hunn, Shiri Salmy and Wunderbar Cultural Projects. The authors respond to our research on democratic process in discursive platforms, notions of autonomy and independence, alternative education, and self-organisation. The collection of this series of texts aims at mapping our research for the DAZIBAO project, and the subsequent various ramifications of our critical thought.