Desertmed. Deserted islands of the Mediterranean

Luigia Lonardelli

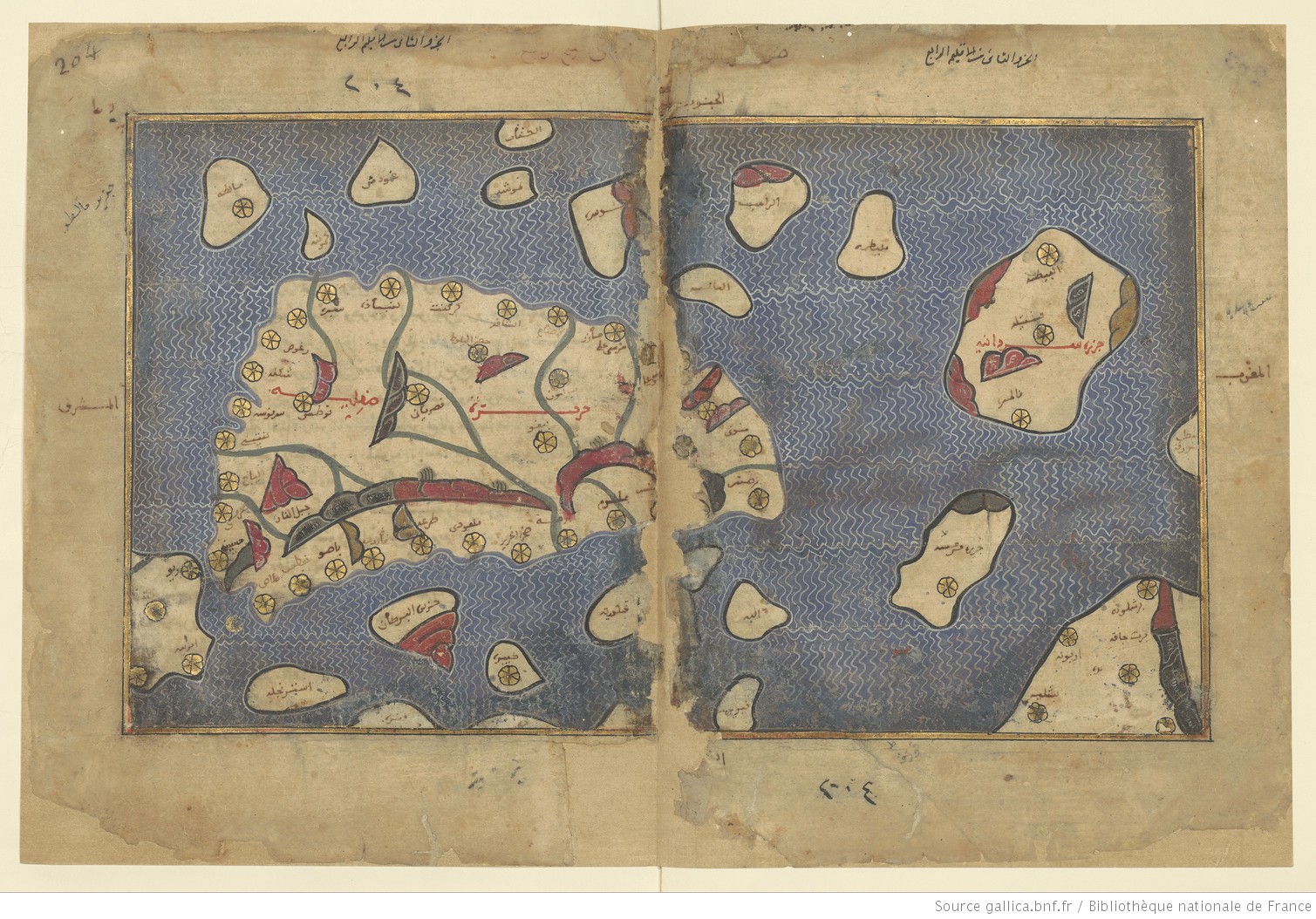

The Mediterranean Sea is 1,136 parasangs long.

It contains around a hundred small and large islands, both inhabited and deserted, which we shall [also] discuss in due time, with the help of the Lord.

Muḥammad ibn Muḥammad al-Idrīsī (سبتة Ceuta, around 1099 – Sicily, 1165)

Islands are a literary place we are accustomed to considering as exotic. Thousands of tales are set on an island, as there is no better place for a story to be told. The acts of finding, reaching and leaving an island are what many narratives revolve around.

In 2008, a group of people embarked upon a journey which saw them travel the Mediterranean Sea and meet many people, by whom they were at times rejected. They followed unconventional routes, and reached strangely-named islands we would have a hard time finding on a map. Those islands preserved confused memories of myths and legends which safeguard the contested, neglected identity of our sea.

The people who embarked upon this journey are photographers, musicians, and thinkers who collected data and measured distances, requested authorisations to disembark and selected routes, looking for different landscapes and alternative forms of organization.

The journey saw the group come across many different types of islands and navigate a rough sea, more suitable for myths than stories. That sea contains dangers, paradoxes and contradictions, and is an accurate metaphor of our time. However, the group was not looking for the sea. Rather, they were interested in what the sea surrounds, namely desert, abandoned islands that are only considered as a temporary source of entertainment without being fully appreciated.

The deserted islands of the Mediterranean became such a short time ago, due either to immigration or to their having become places of entertainment or specialised work. Studying their nature and transformations enabled the group to unveil the hypocrisy these places are surrounded by.

Nowadays, when we speak about the Mediterranean Sea and islands, we feel fear and compassion, as that exotic setting makes us feel guilty. The Mediterranean Sea is where we leave our deepest feelings to settle.

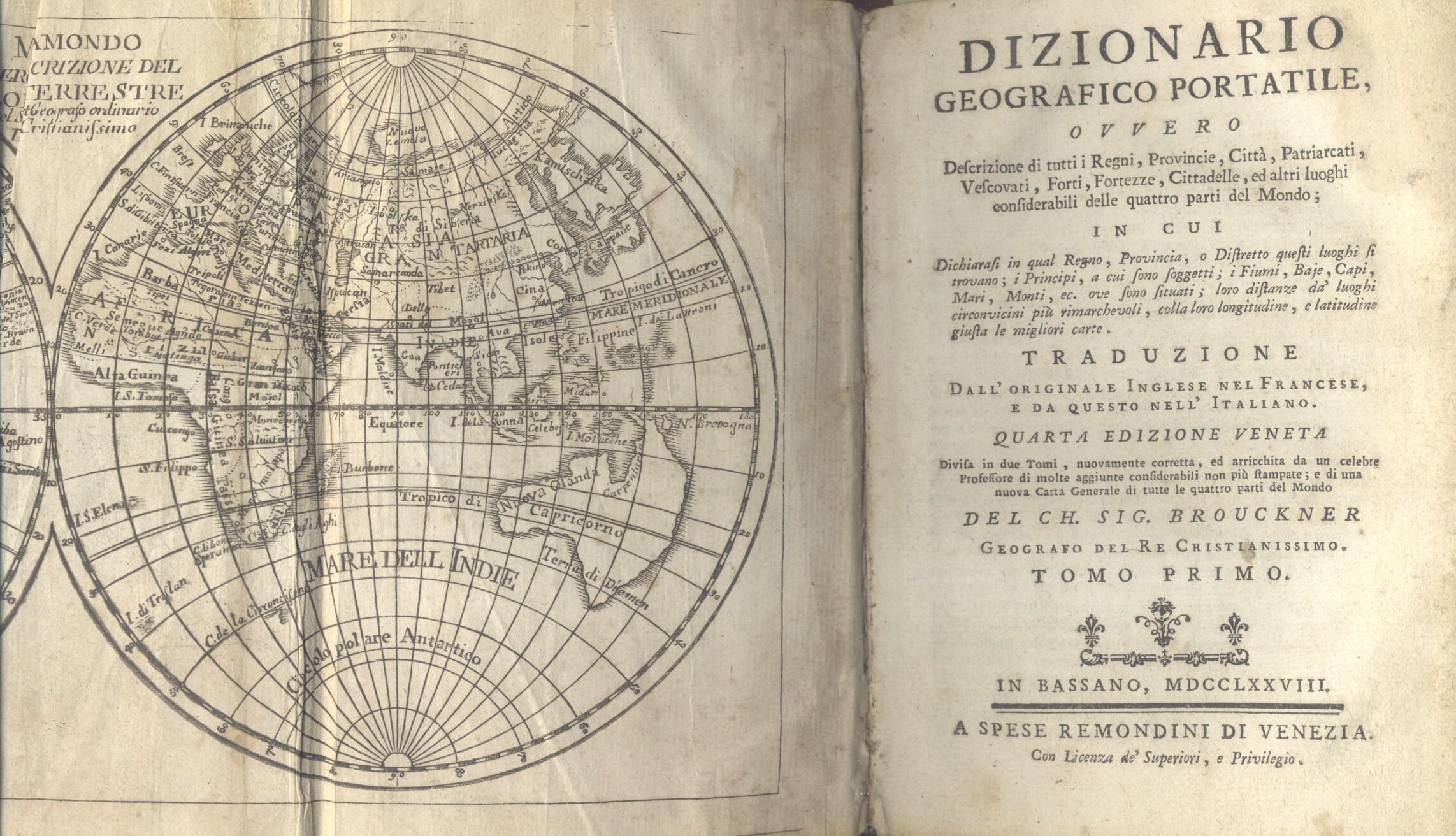

The group, driven by its longing for classification, identified six types of islands: park islands, natural islands, private islands, military-run islands, prison-islands and business-islands. This taxonomy is at the crossroads between an analytical description and a narrative device, and it recalls the descriptions made by ancient geographers, which were both movingly naïve and heroically humanist.

As though it were a club of humanists solely interested in travelling so as to search for something, the group put together blatantly fruitless visions, data and studies enshrining the sehnsucht of an otium time we have been denied.

The group explored forty of those islands. Some cannot be visited, whereas others are difficult to reach, which perpetuates their aura of otherness. They keep being paradises even when their heavenly nature cannot be verified.

The islands they came across are what we wanted them to be, namely natural parks we cannot enter so as to protect them from our sins. They are places of atonement which take no notice of the tragedies surrounding them. They are protected and analysed. They are the object of studies which tell us about what could and should have been.

The islands they reached are not the paradise we had pictured: sometimes they are competed for, sometimes they host factories which temporarily turn them into lively places during the day.

The islands they saw from afar are not what we thought they would be: sometimes they are but small rocks, sometimes they are windswept, unhospitable plains. They are blind spots in Google Maps, places where contours end. There are three hundred small imperfections such as those. Counting them provided the group with food for thought: what is an island, exactly?

Private owners enabled the group to visit their islands only upon invitation and authorisation. Something we believed happened only in other seas is becoming increasingly common in the Mediterranean: Greek islands, also due to the economic crisis, are rapidly changing hands. The fascination of owning an island is directly proportional to its morphology and intrinsic independence. Indeed, the adjective “isolated” comes from the Latin word for island, namely “insula”. On an island, one can fulfill the dream of building a personal republic in accordance with their personal understanding of what an ideal society is.

At times, the group could not disembark, and was left to look at islands from afar, recording their sounds. At times, the group was accompanied by someone, as every island worthy of its name has a guardian. On those occasions, they could but imagine what those who had accompanied them had concealed.

The group carried out its mapping activity as long as it could.

Giulia Di Lenarda, Giuseppe Ielasi, Armin Linke, Amedeo Martegani, Renato Rinaldi and Giovanna Silva were the members of the group. Others joined their quest throughout its course.

The journey accidentally became what we now call “work” for the sake of straightforwardness, and has resulted into a catalogue, a vinyl record, hundreds of pictures, maps, and wishes for the experience never to end. This body of work has already been displayed in several museums, but it keeps growing while awaiting the next reconnaissance.

The name of all this is Desertmed. A project about the deserted islands of the Mediterranean.

Desertmed, albeit indirectly, owes much to Gilles Deleuze’s words: que l’île déserte soit inhabitée reste un pur fait qui tient aux circonstances, c’est-à-dire aux alentours. L’île est ce que la mer entoure, et ce dont on fait le tour, elle est comme un oeuf.

desertmed.org